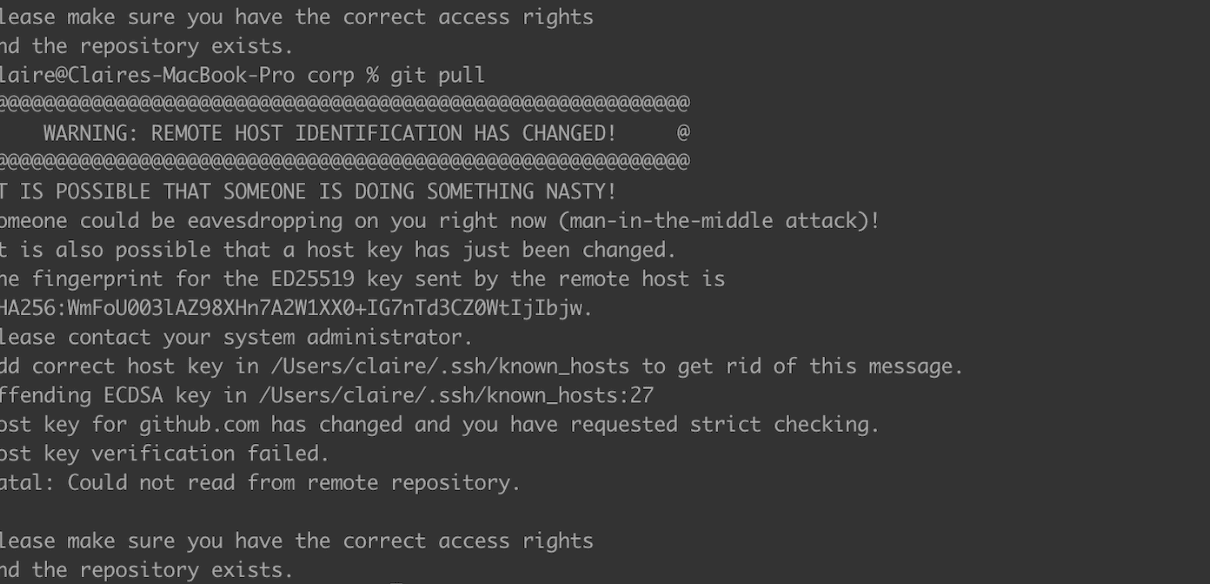

Back in April for RSA 2023, a bunch of Tailscalars were staying at a hotel near the conference center. I wanted to get some work done, and tried pulling code from Github using ssh. An ominous message appeared on my screen.

To be honest, I have never encountered this before. A fingerprint is a way for the machine to recognize the public key of a host from a previously established ssh connection. When you make connections to ssh servers, the fingerprints of every server you connect to is in your known_hosts file in ~/.ssh. The key in the known_hosts file didn't match the key that "Github" gave me. Github had recently changed their ssh RSA host key for security reasons, so maybe this was an opportunity of attack.

I needed to figure out whether the issue was with Github's key or with my connection. To do so, I turned to a popular Tailscale feature: exit nodes, which allow you to forward all your internet traffic through another machine in your tailnet. Luckily I had a Linux box at home on my tailnet that was already configured to be an exit node. I tried accessing Github using ssh with the Linux box, and it connected with no problem. This means that what caused this ssh issue is related not to Github or how I configured my ssh keys, but to the wifi network I was using.

Most VPNs let you route traffic through another computer, but not always one that you control (and that has your known_hosts file saved). What makes using Tailscale even more compelling in this scenario is, to improve bandwidth, I can configure my exit node to only advertise routes to github.com–what we call “subnet routers”.

For example, here's how you can advertise the routes for GitHub's git ingress servers:

$ tailscale set –-advertise-routes="$(curl -fsSL https://api.github.com/meta | jq -r '.git[]' | tr '\n' ',')"

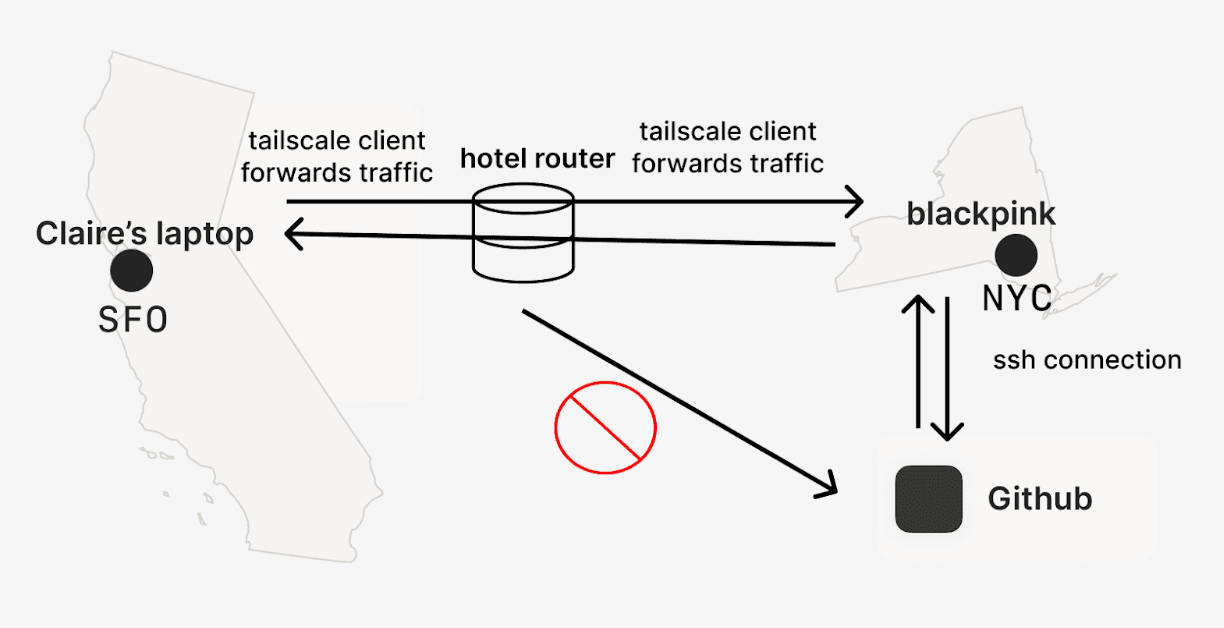

Here’s a diagram showing how I used my exit node. Blackpink is the linux box I used as an exit node. Keep in mind when using exit nodes if latency matters in your use case, you might want to use a machine that’s closer to you.

Also if you don't have an exit node in your tailnet ready to use, you can create a server through a cloud provider with a script that installs Tailscale and adds the machine to your tailnet. If you really don't trust your network, you can do all of this while tethering your phone to your laptop. All of this is pretty tedious so next time you leave your house, just configure a machine for exit node use!

With my exit node configured, the problem at hand was solved. But having a solution wasn’t enough, and we were all pretty curious to find the cause. Perhaps this was a not-very-well hidden attack? Plus, around 40,000 people attended RSA this year, making public hotel networks a perfect attack vector.

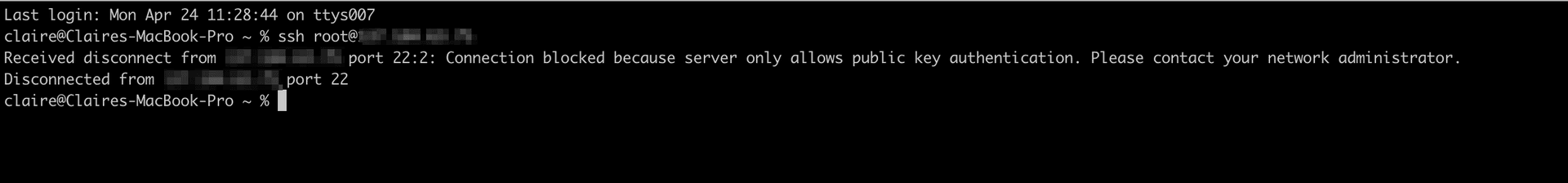

A friend of mine was willing to help me out and had a spare server to play with. The first thing we tried was using ssh-keyscan to see if the fingerprint results were consistent with what my friend expected, and they weren’t. We also forced an output that neither of us expected when I tried to ssh into their server after they turned off password-based login.

A coworker was walking around the hotel and by chance spotted a firewall machine. They were able to discover the feature of the firewall that was allowing the hotel network to intercept ssh connections, and emailed the hotel with instructions on how to turn off the configuration. The hotel immediately followed up and turned off the misconfiguration.

A key takeaway is that exit nodes and subnet routing are very useful tools, especially in places where you don’t trust the network and you probably don’t want to fall into a rabbit hole of investigation.

Many thanks to Andrew and Ryan for helping me figure this out! Thanks Parker for the blog post title.